|

There are three primary obligations of any Christian who calls himself Anglican. The first, of course, is to be baptized with water in the Name of the Trinity. The second is to be confirmed. The third is to receive the Holy Communion regularly. The present discussion concerns the second of these three obligations, Confirmation.

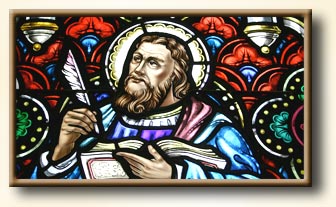

The Order of Confirmation, as found on page 296 of the Book of Common Prayer, is a mixture of Scripture, prayers, questions, vows, and actions, derived from different sources. One or two minor details are as recent as the 1928 revision of the Prayer book. Some were added by the Episcopal Church in its first Prayer Book of 1789. Some go back to the pre-Reformation Sarum Rite of the Church in England. The great prayer in which the Bishop invokes the bestowal of the seven-fold gifts of the Holy Ghost (page 297) can be traced in substance to at least the early third century. Taken as a whole, the Order of Confirmation stands squarely in the most ancient traditions of the Christian Church. The Scripture reading prescribed (page 296), being the words of Saint Luke in the eighth chapter of the Acts of the Apostles, described the actions of Peter and John in Samaria where they laid their hands on the baptized converts so that these new Christians might receive the Holy Ghost. Thus, Confirmation rests upon a sure Scriptural foundation and is entitled to be considered one of the seven Sacraments of the Christian Church, even though, as the Articles of Religion put it, five of them were not directly “ordained of Christ”, as were Baptism and the Lord’s Supper.

The Rite consists essentially of two parts. In one, the candidate “confirms” his baptismal vows. In the second, God “confirms” or strengthens the candidate by the bestowal of the seven great gifts of the Holy Ghost -- wisdom, understanding, counsel, “ghostly” or spiritual strength, knowledge, godliness and holy fear.

In the Anglican tradition, only a bishop as the successor of the Apostles, can lay hands upon a person in Confirmation. Anglicanism also holds that no one should be admitted to the Holy Communion until he is prepared for this great act of union with Christ by being confirmed. Baptism and Confirmation were originally joined together in one ceremony, as a general rule. Some parts of the Church Catholic still conjoin them. However, Anglican practice has always been to separate them in time, again as a general rule: Baptism takes place in infancy, Confirmation when the child has reached some years of discretion and understanding.

Confirmation is not an act which by some magic turns a person into a good and obedient Christian and child of God. It is an act, like Baptism and Holy Communion, in which God reaches out to us, ready and eager to help us. But unless we reach back and accept and use what is offered, there is no helpful and beneficial contact. In Confirmation, we are offered the great presence and gifts of God the Holy Ghost. They are ever thereafter at our disposal, sources of strength in all our efforts to be perfect, “even as your Father which is in heaven is perfect”.

|